Editor’s Note: Two weeks ago I turned 30, and feel it’s the right time to share a story that defined my twenties. Looking back, it was this trip that flipped the switch in my head that said “yeah…I guess I can try journalism?” I’ve published facets of this story already here and here. But this is a more personal version, one that I first wrote in 2019 and just kinda held on to. As it turns out, publishers have little interest in some guy nobody has heard of’s travelogue to a place nobody’s heard of to go looking for a guy nobody’s heard of.

June and I have been driving all day, moving north up the Wisconsin side of Lake Michigan. We’re headed to the Upper Peninsula, the remote piece of land stretching like a curved finger from the top of Wisconsin, resting on top of Michigan’s mainland mitten, and I’ve decided I’m going to find a man named Jeff Cowell.

It’s becoming one of those beautiful sunsets during late summer, that sliver of time when you start mistaking the warm sun and sticky air as permanent. We cross into Michigan at the golden hour and pull into Lake Antoine’s campsite right before the park office closes. We pick out Lot #6 for the night: a patch of dirt, a picnic table, and a firepit. After setting up our tent, June and I walk across the campground to the lake. We sit in tiny lawn chairs on the beach, drink a beer, and watch the green hills light up, then darken, as the sun sets. What strikes me most is how quiet it is. We’re very far from Chicago, and I’m thankful that the distance feels like insulation.

I’m not sure how Lake Antoine is pronounced. I want to say “An-twan”, but then June tells me she heard someone call it “An-toyn”, and then, with a Yooper accent, it comes across more like “An-Twine.” June and I became friends going to school in New Orleans, a place where nothing is pronounced the way you think it is.

2017 was the first time I heard Jeff Cowell’s 1975 album Lucky Strikes and Liquid Gold. Since then, I’ve become an obsessive. It’s a sparse proto-alt country record about isolation and the people we rely on. His songwriting grapples with intimacy-- he keeps his distance from others: “can’t reach Jake, he’s too far away.” Elsewhere, he receives a mandate to be connected to others: “When you see me comin’ down the road, help me with my heavy load.” Cowell belongs with musical peers like Neil Young (the album shares pedal steel folk and drifter ideology with Tonight’s the Night) and Townes Van Zandt. But Jeff Cowell is not well known at all. He is mysterious and his failure is mysterious. I knew nothing about the Upper Peninsula except for one guy’s sketchings of it: its forests and bars, the sides of its highways and how the wind feels, how people there lived. On the album cover, Jeff stands with one foot on a park bench, facing the camera, black and white trees behind him. Even in the photo, Jeff’s ambiguity in facing the camera is its own decision-- he neither embraces its gaze nor looks away fully, giving a smirk, a barrier.

I’m nervous. I mean, what I’m doing is kind of weird? I’m tracking someone down. It’s definitely nuts. Jeff Cowell is a private citizen. He put out a couple albums in the 1970s, then the paper trail disappears. He has no online presence. I haven’t been able to find a way to get in contact with him. He’s got no email that I can find. No phone number. No Twitter. Nothing. Not even considering that he might not want to be found, I don’t know how I’ll find him.

Our campsite neighbor at Lake Antoine is a tall, gregarious Viking of a man named Bill. He’s got a massive white beard and a tiny white dog. Bill explains that he lives and works in Quinnesec, the town just south of the campsite. He’s the city worker who does everything from mixing concrete to fixing leaky pipes, depending on the day. And he’s the lead singer in a rock band. His daughter bikes around their trailer, telling us that she’s at every rehearsal and show and she’s their #1 fan. He’s bummed we won’t be able to make it to his show at the Blues Fest in Escanaba. It seems like a stroke of luck to be camping next door to a local musician, so I ask him if he knows who Jeff Cowell is. Bill says that he’s heard the name, but not too much more than that. I ask if he knows any country western bars in the area, and the only one he can think of closed down. He recommends an all-you-can-eat wings bar in Iron Mountain for dinner.

Lake Antoine’s campsite is situated right next to the two-lane Lake Antoine Road. I keep jolting awake in the middle of the night. At first I figure I’m just adjusting to tent life. But then 20 minutes later, it happens again, heart jumping out of my ribcage. And then an hour later, the same thing. Lying somewhere between awake and asleep, I start to piece together that what’s been waking me are logging trucks. I can feel them thunder down the road, shaking the ground as they fly through the dark, 20 feet from us. The trees these trucks carry are as long as city buses. If a tree fell off a truck it would crush me like a bug from a boot.

—----

I wake up sore and groggy, unzipping the tent and falling out into a sunny summer U.P. morning. We pack up and head in to Iron Mountain. Our first stop is a coffee shop— a big sanitized space with a bygone vibe of earth tones and Live.Laugh.Love-inspired decor, completely out of step with this Rust Belt former mining town. June wants to go to the Cornish Pump Museum because she’s a nerd like me but in a completely different way, so after coffee we begin our trek north up the hilly city blocks to the museum.

The small museum literally surrounds the pump, which is the largest steam pump built in America. The machine not only made mining possible— it made mining lucrative. There was once a lot of wealth in the Upper Peninsula. The strange piece of northern land was a place of infinite resources– until they ran out. Mining and Logging sank their teeth into Michigan in the late 1800’s. Their exports built up a lot of America. The first ever mineral rush, predating the California gold rush, happened in Copper Harbor, the northern peninsula that juts out into Lake Superior. At one point the richest man in America was a Yooper, and Copper Harbor was more populous than Detroit. Noted antisemite Henry Ford even built a Ford Plant in Iron Mountain. Combined with Detroit’s manufacturing, the Upper Peninsula’s extractable resources helped define Michigan’s legacy as a hub of American industry. Now all that’s left are the old ladies who run the museums.

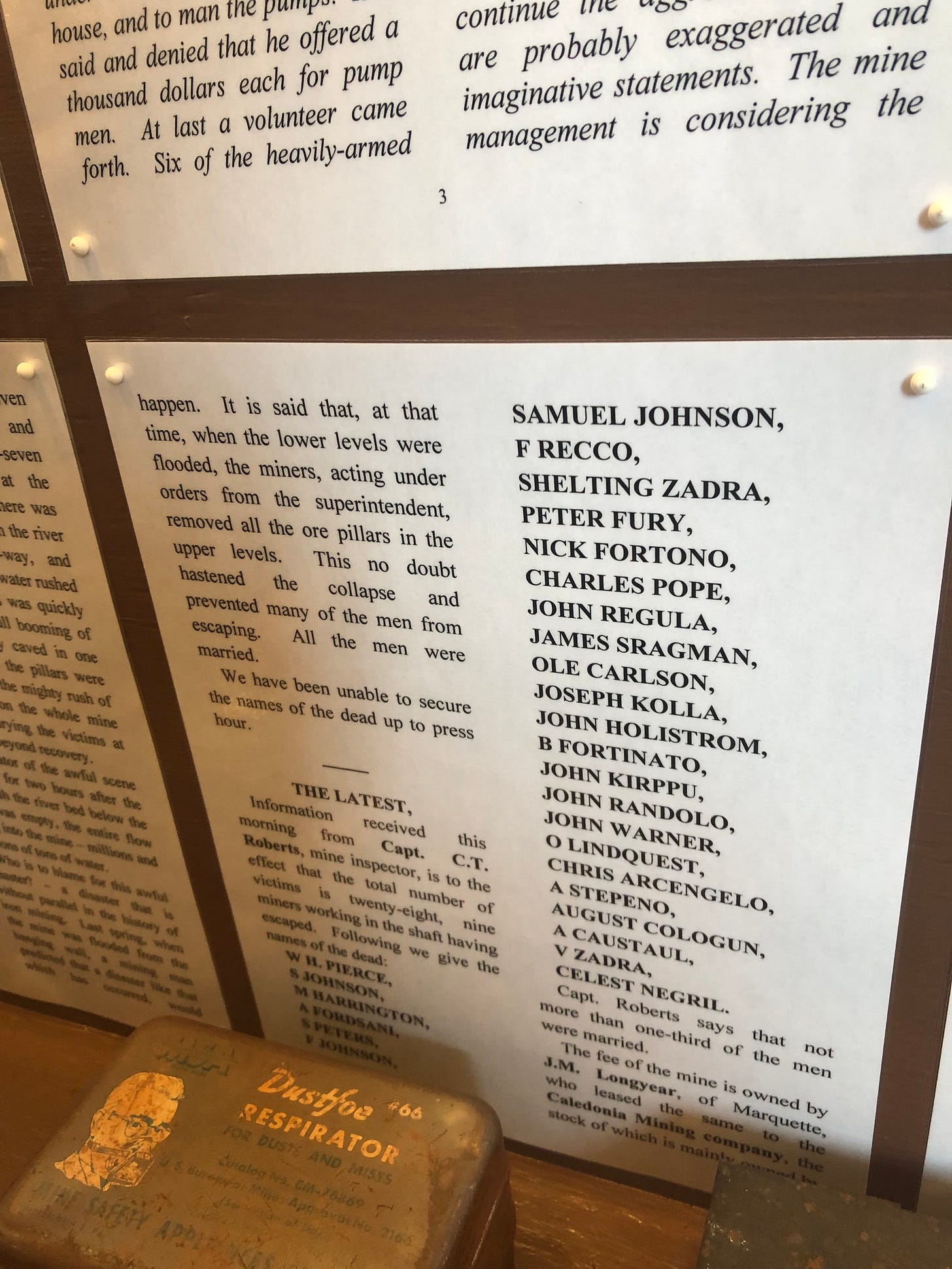

The engineering and science behind how the pump works (which I assume is impressive because there’s a museum about it) was lost on me, as I’m a simple-minded fellow. What interested me more were the news clippings lining the walls, recounting the terrible ways that miners died. As is the case with most industrial labor, what was a boon for the owners was arduous and gothically lethal for the workers. Here’s a newspaper headline that describes a lot of men dying: “The Mansfield Mine Horror: 37 Miners Drowned Thursday Night” (1893). And here’s one that describes just one man dying, but in grotesque detail: “A Fatal Blast: James Harris Met With an Awful Accident Which Resulted in Death...LEAVES A LARGE FAMILY...Hand Blown Off. Piece of Rock Penetrates the Brain. Both Eyes Filled With Powder. Lived Two Hours After Accident and Suffered Untold Agony” (1896).

Encircling the massive Cornish Pump are flags meant to signify all the different ethnic groups that worked in the mines. English (Cornish), Welsh, Norwegian, Italian, Irish. The Upper Peninsula is notable in that it was one of the earliest American examples of (relatively) successful ethnic melding. Still, I was confused to see that farthest to one side was a smaller Israeli flag. The mine was both constructed and ceased operations before the modern state of Israel was established. Was this the museum’s attempt to say there were Jews? We asked the woman who ran the museum and she said that yes, at one point there was a small Jewish population in Iron Mountain. She tells us to visit the cemetery to see the Jewish section, and mentions offhand that there is a synagogue in town.

I ask her if she knows someone named Jeff Cowell. She takes a beat, examining me, and says that yes she’s heard of him, wondering aloud if he’s the one who writes poetry, which she says with a perfectly Midwestern hint of contempt. I tell her that I’m hoping to find him and she whips around, saying that she can look up his number and address in the phone book. It felt almost like a cheat code. I give the phone number a try after we leave the museum, but it’s disconnected. However, we do have a potential address.

The sun is trekking across the sky as we walk back down the hill into Iron Mountain’s main stretch. We stop at a record store called Music Tree. The fella that works there, PJ, seems unhappy with his lot but unwilling to do anything about it. He tells us he has a second job as a DJ. The big song at the time is Old Town Road, so I ask him how he feels about it. PJ smiles and admits he does like it.

PJ says he lived in the Chicago suburbs for a time but didn’t like it. He hasn’t heard of Jeff Cowell at all, which surprises me, and he points to the music from local U.P. Musicians, a stack of two CDs sitting next to the cash register. One of them is Bill from the campsite’s band. When we ask about the coffeeshop we were at earlier, PJ laughs and says that there are tons of coffeeshops in town because everyone “gets drunk all night and needs a place to sober up before work in the morning.” Ultimately not the most optimistic outlook, but perhaps realistic.

We catch the cemetery foreman on his way to lunch. His directions to the Jewish part are more like a riddle than anything (“where the road slopes, there’s a stand of white pine trees…”). As we drive around the cemetery, it becomes clear that the riddle has bested us. We loop back to where we started. The sun idles at the top of the sky and yellow wildflowers sway in the hot breeze. We scan the fields of crosses and Scandinavian names, searching for a Star of David. And then June stops the car. “Wait, look at that” she says, pointing to a headstone delineating a family plot, and as my brain puts the letters together, my heart sinks. It’s Jeff Cowell’s grave.

Part Two next week…